A recent study found that individuals with two copies of the APOE4 gene almost always develop signs of Alzheimer’s disease. This gene has long been associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s, but the study suggests that for those with two copies, it is an underlying cause of the disease. The findings, published in Nature Medicine, reveal that people with two copies of the gene develop Alzheimer’s earlier than those with other APOE gene variants. Alzheimer’s disease affects around 7.8 million people in the European Union and is characterized by a decline in memory function and thinking skills.

Dr. Juan Fortea, the lead author of the study from the Sant Pau Research Institute in Barcelona, Spain, stated that approximately 15% of Alzheimer’s patients carry two copies of the gene. This means that those cases can be directly attributed to genetics. The discovery has profound implications and highlights the importance of developing treatments that specifically target the APOE4 gene. Fortea emphasized that while the gene has been known for over 30 years to increase the risk of Alzheimer’s, the study now shows that virtually all individuals with two copies of the gene develop Alzheimer’s biology.

Genetics play a crucial role in Alzheimer’s disease, with a few genes known to cause rare early-onset forms of the condition. However, Alzheimer’s most commonly occurs after the age of 65, with the APOE gene playing a role in late-onset cases. While most people carry the APOE3 variant, which does not significantly impact Alzheimer’s risk, some have APOE2, which offers some protection against the disease. APOE4 is considered the major genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s, with individuals having two copies at a higher risk.

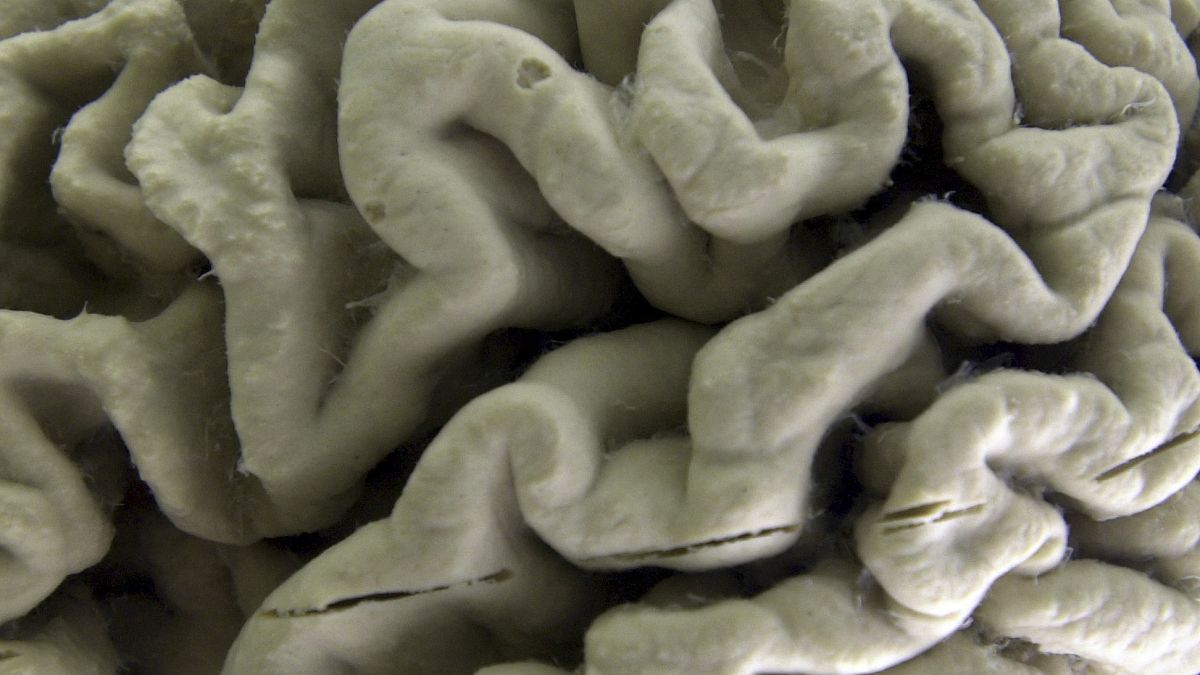

The study utilized data from thousands of individuals and examined brain samples to identify potential correlations between genetics and Alzheimer’s. People with two copies of the APOE4 gene showed an increased accumulation of amyloid in the brain, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s, at a younger age compared to those with one copy. By age 65, nearly three-quarters of double carriers had significant plaque buildup in the brain, leading to initial Alzheimer’s symptoms earlier in life. The underlying biology of the disease in these individuals resembled that of young inherited types of Alzheimer’s.

Dr. Eliezer Masliah of the National Institute on Aging described the findings as more akin to a familial form of Alzheimer’s rather than just a risk factor. Research is ongoing to develop treatments that specifically target the APOE4 gene, with a focus on gene therapy or new drugs. It is crucial to understand the effects of APOE4 in diverse populations, as previous studies have mainly focused on individuals of European ancestry. While the study sheds light on the genetic component of Alzheimer’s, experts caution against rushing to get genetic tests, as the APOE4 gene duo is not responsible for the majority of cases.

Dr. Reisa Sperling from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston emphasized the importance of not alarming individuals with a family history of Alzheimer’s. While the study highlights the significance of the APOE4 gene in certain cases, it is essential to remember that Alzheimer’s is a complex disease with various contributing factors. Developing treatments that target specific genetic markers may offer new possibilities in combating Alzheimer’s and improving outcomes for affected individuals. It underscores the necessity of further research into understanding the genetic basis of the disease and exploring targeted therapies to address the underlying causes of Alzheimer’s.